kindesk4042

ABC Compass follows Pulitzer Prize-winner and beloved Australian author Geraldine Brooks as she returns to Flinders Island where she wrote her memoir, Memorial Days.

Geraldine Brooks was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 2006 for her novel March. Her novels People of the Book, Caleb’s Crossing, The Secret Chord and Horse all were New York Times Bestsellers. Her first novel, Year of Wonders is an an international bestseller, translated into more than 25 languages and currently optioned for a limited series by Olivia Coleman’s production company. She is also the author of the nonfiction works Nine Parts of Desire, Foreign Correspondence and The Idea of Home. Her latest book, Memorial Days, was published January 24 in Australia, and February 4 in the United States.

A heartrending and beautiful memoir of sudden loss and a journey towards peace from Geraldine Brooks, the bestselling, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Horse.

Photo credit: Elizabeth Cecil

Many cultural and religious traditions expect those who are grieving to step away from the world. In contemporary life, we are more often met with red tape and to-do lists. This is exactly what happened to Geraldine Brooks when her partner of more than three decades, Tony Horwitz – just sixty years old and, to her knowledge, vigorous and healthy – collapsed and died on a Washington, D. C. sidewalk.

After spending their early years together in conflict zones as foreign correspondents, Geraldine and Tony settled down to raise two boys on Martha’s Vineyard. The life they built was one of meaningful work, good humor, and tenderness, as they spent their days writing and their evenings cooking family dinners or watching the sun set with friends at the beach. But all of this ended abruptly when, on Memorial Day 2019, Geraldine received the phone call we all dread. The demands were immediate and many. Without space to grieve, the sudden loss became a yawning gulf.

Three years later, she booked a flight to a remote island off the coast of Australia with the intention of finally giving herself the time to mourn. In a shack on a pristine, rugged coast she often went days without seeing another person. There, she pondered the various ways in which cultures grieve and what rituals of her own might help to rebuild a life around the void of Tony’s death.

A spare and profoundly moving memoir that joins the classics of the genre, Memorial Days is a portrait of a larger-than-life man and a timeless love between souls that exquisitely captures the joy, agony, and mystery of life.

Praise

“Warm and life-affirming, this brilliant book has its own restorative beauty.”

–People, Book of the Month

“Wielding precise and often beautiful language and, in the most graceful way possible, pointing a way forward. A rich account of marriage and mourning.” –The Washington Post

“Deftly availing herself of both her work as a journalist and a novelist, Brooks tracks the geography of grief with patience and grace as she comes to terms with the ongoing nature of outliving the ones you love most…. Her memoir is certainly a testament to her own unique loss, but it’s moreover a lifeline to others who will find themselves in this familiar, shattered landscape of grief.”

–Los Angeles Times

”She returned to her native Australia, to an isolated shack on tiny, sparsely populated Flinders Island to face her loss by writing this book: the story of Horwitz’s accomplished life and untimely death… the narrative of their wonderful relationship, which began when they met as students at Columbia Journalism School and could almost be a treatment for a rom-com.” –The Boston Globe

“Brooks seems brittle still, but writing is her way through, …And she’s such an adroit, un-maudlin observer that “Memorial Days” does transfix, and stick.” –New York Times

“A spectacular ode to grieving and an elegant homage to marriage…A masterpiece.” –The Georgetowner

Viking Books asks Geraldine Brooks some fascinating questions about her new novel, Horse.

HORSE is based on a real-life racehorse named Lexington, one of the most famous thoroughbreds in American history. How did you learn about him?

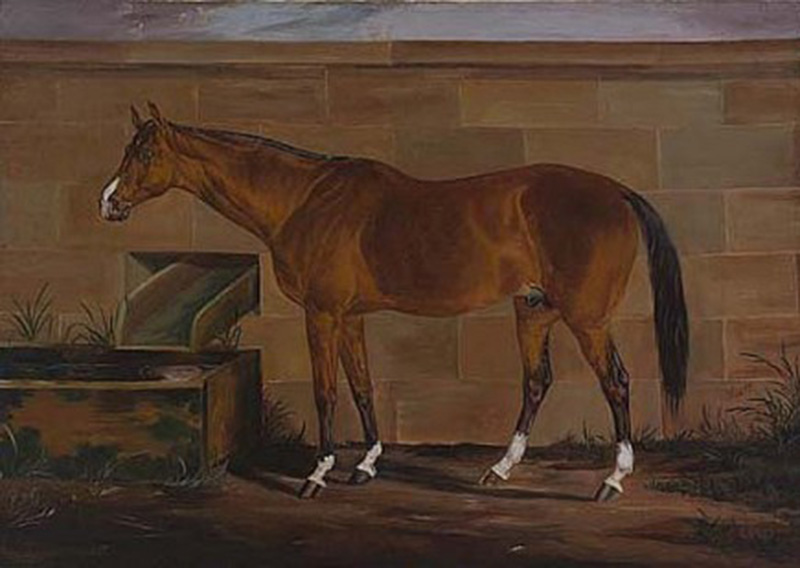

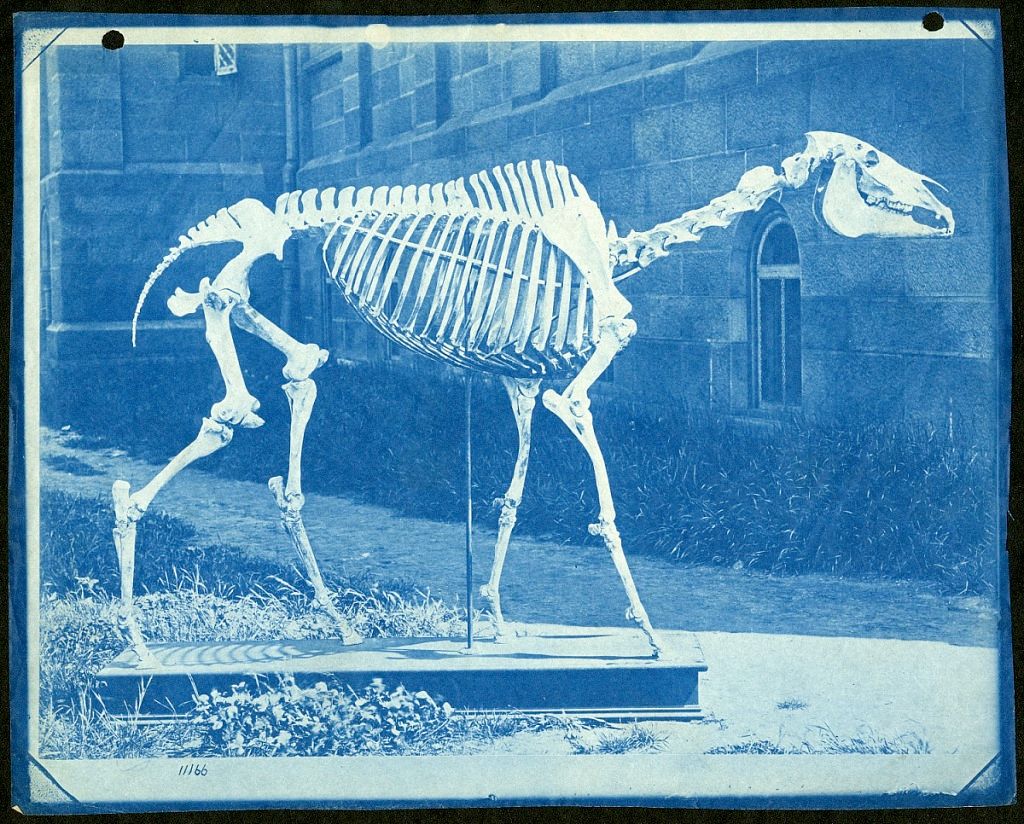

I had just published my novel, Caleb’s Crossing, which was partially researched at Plimoth Plantation, and the curators there had invited me to a lunch, at which they suggested I might want to write a novel based on a young woman from the early Plimoth settlement. It was clear to me that this would be too close to the character I’d already created in Caleb’s Crossing but from across the table I began to catch snatches of a different conversation. An executive from the Smithsonian was describing how he had just overseen delivery of Lexington’s skeleton from Washington DC to the International Museum of the Horse in Kentucky, where it would be the centerpiece on the history of thoroughbred racing in the US. As he related the horse’s extraordinary life story, I became fascinated, and by the time he got to the horse’s fate in the Civil War, I knew that my next book wouldn’t be about a settler in Plimoth, but about this horse.

Why the title?

When Lexington died, the horse was so beloved he was given a ceremonial burial, complete with a horse-sized coffin. Later, it was suggested that his skeleton be disinterred and gifted to the Smithsonian. It stood in pride of place there for many years. But as the horse’s fame waned and the museum’s emphasis switched from displaying curiosities to advancing scientific knowledge, Lexington’s individual story became less important, until the skeleton stood in the Hall of Osteology along with those of other species, simply an example of “equus caballus”, or “Horse.” Eventually it was relegated to the attic of the natural History Museum and all but forgotten.

It’s clear in the novel how central horseracing was in the 1850s, a passion as much in the North as the South, among Black Americans as White Americans. Why do you think it was so popular?

Before the Civil War and the Jim Crow era that followed Reconstruction, the racetrack was an integrated space, where all classes and colors mingled. Horseracing was the popular pastime of the 1800s, with crowds of twenty thousand or more packing racetracks to watch famous rivals such as Eclipse and Fashion, Grey Eagle and Wagner, and thousands of fans following the outcome in the lively turf press of the day. Of New York’s three main newspapers of the era, two were devoted entirely to horseracing. America was an agrarian culture; even most townsfolk were only a generation removed from the land. Races happened everywhere. Andrew Jackson raced his horse in the streets of Washington DC; many towns hosted quarter mile sprints on their Main Streets, and farmers of modest means dreamed of breeding the next champion. Meanwhile, the wealthy built racetracks on their plantations and saw in their thoroughbreds a reflection of their own prestige.

What is known about the enslaved people whose skills the racing business was built on? What sources did you have, and how much was left to the imagination?

Horseracing relied on the plundered labor of highly skilled Black trainers, jockeys and grooms. Their centrality is evident in the surviving correspondence of elite White horse breeders, who counted on the expertise of these men. These letters, as well as reporting in the turf press, reveal deference to the knowledge and skill of trainers such as Hark, Ansel Williamson and Charles Stewart and jockeys such as Abe Hawkins and Cato. These were great professionals who, within a brutal system, wrested a degree of personal agency not available to most enslaved people, including acquiring property and traveling widely throughout the country. Unfortunately, most of what we know of them is distorted through a White lens: Charles Stewart, for example, related his life story to a White woman and while the account is rich in detail, it is likely that he self-censored aspects that reflected badly on her forebears.

The central story involves Jarrett, an enslaved boy, and Lexington, the racehorse he raises and trains. What inspired his character and his story?

There are detailed accounts of a lost painting by the artist Thomas J. Scott (who is also an important character in the novel) depicting Lexington “being led by black Jarret, his groom” while the horse was at Woodburn Stud, which was perhaps the preeminent livestock breeding operation in America at the time. I was unable to find any biographical detail on Jarret, so I created his character based on records I could find about two highly accomplished Black horsemen who, though enslaved, were in charge of Woodburn’s thoroughbred operations: the trainer Ansel Williamson and the jockey and trainer Edward D. Brown.

The novel features a nearly contemporary storyline, set right before the pandemic, and an interracial relationship at the heart of it. As a historical novelist, why did you choose to write in the present day?

Just as my novel People of the Book has a contemporary thread in dialogue with its historical core, I wanted this novel to take us into the modern laboratories at the Smithsonian where bones are studied and artworks are evaluated. As I researched the historical spine of the novel it became clear to me that the story I’d thought would be about a racehorse was also a story about race, and as White supremacists rioted in Charlottesville and George Floyd died under the knee of a White police officer, I knew I could not deal with racism in the past and not address its loud and tragic echoes in the present.

You made another discovery related to the horse while you were researching at the Smithsonian, but this one was about art, not science.

Yes. One of the best surviving portraits of Lexington, painted by Thomas Scott, was given to the Smithsonian in a bequest from the pioneering gallerist, Martha Jackson. She was a friend of Pollock and DeKooning and a champion of avant garde art in 1950s New York City. It’s the only traditional, representational painting in her bequest–very different from the art she loved and collected. The mystery of why that painting might have mattered to Martha brings the novel into the turbulent, bohemian, post-war art world at the birth of abstract expressionism.

Who are the famous horses who descend from Lexington?

Ulysses S. Grant’s favorite horse, Cincinnati; the horse Preakness after whom the stakes race is named and two other Preakness winners; nine of the first fifteen Travers Stakes winners,; Asteroid, who was undefeated; Kentucky, who is in the US Racing Hall of Fame. Lexington sired 236 winners at a time when racing was disrupted by the Civil War and many thoroughbreds were requisitioned as warhorses. He appears in the bloodlines of many of the greatest racehorses even today.

You dedicate the novel to your late husband, the writer Tony Horwitz, and write in your Afterword that you traveled together to Kentucky, where your research often intersected in intriguing ways. Would you describe some of those intersections?

Tony was researching the travels of Frederick Law Olmsted just before the Civil War. Olmsted was interested in the views of the emancipationist Cassius Clay, who also happened to be the son-in-law of Lexington’s breeder, so we traveled together to Clay’s estate, White Hall. Tony also knew his way around the rich archival sources in Kentucky and was able to help me unearth a Civil War journal by the chaplain of Thomas Scott’s unit, which contained a detailed memoir of the two men’s relationship, forged in field hospitals caring for the wounded.

You ride horses and thank your horse Valentine and her companion who “were daily inspirations.” When did you begin riding?

Late! I was in my 50s when I took my first riding lesson, a time when knitting lessons might perhaps have been a more prudent choice. I’m still not a very good rider, but there’s so much more to horses. They’re exquisitely sensitive animals who can teach us a lot about ourselves, about group dynamics, and about leadership. Valentine and I have volunteered in a therapeutic riding program for children with autism and sometimes the relationship between child and horse verges on the miraculous. That’s why it’s tragic that so many racehorses are used up and destroyed before they’re five. My horse is twenty-six and she still has so much to give.

A discarded painting in a junk pile, a skeleton in an attic, and the greatest racehorse in American history: from these strands, a Pulitzer Prize winner braids a sweeping story of spirit, obsession, and injustice across American history.

Click here to read Geraldine’s author Q&A for Horse.

Kentucky, 1850

An enslaved groom named Jarret and a bay foal forge a bond of understanding that will carry the horse to record-setting victories across the South. When the nation erupts in civil war, an itinerant young artist who has made his name on paintings of the racehorse takes up arms for the Union.

On a perilous night, he reunites with the stallion and his groom, very far from the glamor of any racetrack.

New York City, 1954

Martha Jackson, a gallery owner celebrated for taking risks on edgy contemporary painters, becomes obsessed with a nineteenth-century equestrian oil painting of mysterious provenance.

Washington, DC, 2019

Jess, a Smithsonian scientist from Australia, and Theo, a Nigerian-American art historian, find themselves unexpectedly connected through their shared interest in the horse—one studying the stallion’s bones for clues to his power and endurance, the other uncovering the lost history of the unsung Black horsemen who were critical to his racing success. Based on the remarkable true story of the record-breaking thoroughbred, Lexington, who became America’s greatest stud sire, Horse is a gripping, multi-layered reckoning with the legacy of enslavement and racism in America.

International Editions

A rich and utterly absorbing novel about the life of King David, from the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of People of the Book and March

With more than two million copies of her novels sold, New York Times bestselling author Geraldine Brooks has achieved both popular and critical acclaim. Now, Brooks takes on one of literature’s richest and most enigmatic figures: a man who shimmers between history and legend. Peeling away the myth to bring David to life in Second Iron Age Israel, Brooks traces the arc of his journey from obscurity to fame, from shepherd to soldier, from hero to traitor, from beloved king to murderous despot and into his remorseful and diminished dotage.

The Secret Chord provides new context for some of the best-known episodes of David’s life while also focusing on others, even more remarkable and emotionally intense, that have been neglected. We see David through the eyes of those who love him or fear him—from the prophet Natan, voice of his conscience, to his wives Mikal, Avigail, and Batsheva, and finally to Solomon, the late-born son who redeems his Lear-like old age. Brooks has an uncanny ability to hear and transform characters from history, and this beautifully written, unvarnished saga of faith, desire, family, ambition, betrayal, and power will enthrall her many fans.

Reviews

“In her gorgeously written novel of ambition, courage, retribution, and triumph, Brooks imagines the life and character of King David…The language, clear and precise throughout, turns soaringly poetic when

describing music or the glory of David’s city…the novel feels simultaneously ancient, accessible, and timeless.” –Booklist-starred review

“What Mary Renault did with Alexander the Great, Geraldine Brooks has done with King David: breathed life into an ancient hero. Haunting, exciting and as satisfying in structure as a completed Rubik’s Cube.” — Tom Holland

“Brooks evokes times and place with keenly drawn detail. . .with the verve of an adroit storyteller. . .Ambitious and psychologically astute.” — Publisher’s Weekly

“Brooks continues to explore the meaning of faith and religion in ordinary life. . .she skillfully retells David’s story through the eyes of Natan. . .Of just as much interest as Brooks’ view of the politically astute lion in winter are her portraits of characters who are somewhat thinly fleshed in their biblical accounts, such as Batsheva, Yoav, Avner, even Avshalom. A skillful reimaging gracefully and intelligently told.” – Kirkus Reviews

Buy Links

A double rescue in wartime Sarajevo.

By Geraldine Brooks

When the Axis powers conquered and divided Yugoslavia, in the spring of 1941, Sarajevo did not fare well. The city cradled by mountains that Rebecca West once described as like “an opening flower” suddenly found itself absorbed into the Nazi puppet state of Croatia, its tolerant, cosmopolitan culture crushed by the invading German Army and the Croatian Fascist Ustashe. Hitler’s ally, Ante Pavelic, who had headed the Ustashe through the nineteen-thirties, proclaimed that his new state must be “cleansed” of Jews and Serbs: “Not a stone upon a stone will remain of what once belonged to them.”

The terror began on April 16th, when the German Army entered Sarajevo and sacked the city’s eight synagogues. The Sarajevo pinkas, a complete record of the Jewish community from its earliest days, was sent to Prague and was never recovered. Deportations followed. Jews, Gypsies, and Serbian resisters turned frantically to sympathetic Muslim or Croat neighbors to hide them. Fear of denunciation spread through the city, penetrating every workplace, even the imposing neo-Renaissance halls of the Bosnian National Museum.

With her critically acclaimed and bestselling novel Year of Wonders, Geraldine Brooks was praised for her passionate rendering and careful research in vividly imagining the effects of the bubonic plague on a small English village in the seventeenth century. Now, Brooks turns her talents to exploring the devastation and moral complexities of the Civil War through her brilliantly imagined tale of Mr. March, the absent father from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. In Mr. March, Brooks has created a conflicted and deeply sensitive man, a father who is struggling to reconcile duty to his fellow man with duty to his family against the backdrop of one of the most grim periods in American history.

With her critically acclaimed and bestselling novel Year of Wonders, Geraldine Brooks was praised for her passionate rendering and careful research in vividly imagining the effects of the bubonic plague on a small English village in the seventeenth century. Now, Brooks turns her talents to exploring the devastation and moral complexities of the Civil War through her brilliantly imagined tale of Mr. March, the absent father from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. In Mr. March, Brooks has created a conflicted and deeply sensitive man, a father who is struggling to reconcile duty to his fellow man with duty to his family against the backdrop of one of the most grim periods in American history.

October 21, 1861. March, an army chaplain, has just survived a brush with death as his unit crossed the Potomac and experienced the small but terrible battle of Ball’s Bluff. But when he sits down to write his daily missive to his beloved wife, Marmee, he does not talk of the death and destruction around him, but of clouds “emboss[ing] the sky,” his longing for home, and how he misses his four beautiful daughters. “I never promised I would write the truth,” he admits, if only to himself.

When he first enlisted, March was an idealistic man. He knew, above all else, that fighting this war for the Union cause was right and just. But he had not expected he would begin a journey through hell on earth, where the lines between right and wrong, good and evil, were too often blurred.

For now, however, he has no choice but to press on. He is directed to a makeshift hospital, an old estate he finds strangely familiar. It was here, more than twenty years earlier, that he first met Grace, a beautiful, literate slave. She was the woman who provided his first kiss and who changed the course of his life.

Now, he finds himself back at the Clement estate, and what was once the most beautiful place he had ever seen has been transformed by the ugliness of war. However, March’s sojourn there is brief and he finds himself reassigned to set up a school on one of the liberated plantations, Oak Landing—a disastrous posting that leaves him all but dead.

Though rescued and delivered to a Washington hospital where his physical health improves, March is a broken man, haunted by all he has witnessed and “a conscience ablaze with guilt” over the many people he feels he has failed. And when it is time for him to leave he finds he does not want to return home. He turns to Grace, whom he has encountered once again, for guidance. “None of us is without sin,” she tells him. “Go home, Mr. March.” So, March returns to his wife and daughters, and though he is tormented by the past and worried for his country’s future, the present, at least, is certain: he is home, he is a father again, and for now, that will be enough.

Questions for Discussion

1) Throughout the novel, March and Marmee, although devoted to one another, seem to misunderstand each other quite a bit and often do not tell each other the complete truth. Discuss examples of where this happens and how things may have turned out differently, for better or worse, had they been completely honest. Are there times when it is best not to tell our loved ones the truth?

2) The causes of the American Civil War were multiple and overlapping. What was your opinion of the war when you first came to the novel, and has it changed at all since reading March?

3) March’s relationships with both Marmee and Grace are pivotal in his life. Discuss the differences between these two relationships and how they help to shape March, his worldview, and his future. What other people and events were pivotal in shaping March’s beliefs?

4) Do you think it was the right decision for March to have supported, financially or morally, the northern abolitionist John Brown? Brown’s tactics were controversial, but did the ends justify the means?

5) “If war can ever be said to be just, then this war is so; it is action for a moral cause, with the most rigorous of intellectual underpinnings. And yet everywhere I turn, I see injustice done in the waging of it,” says March (p. 65). Do you think that March still believes the war is just by the end of the novel? Why or why not?

6) What is your opinion of March’s enlisting? Should he have stayed home with his family? How do we decide when to put our principles ahead of our personal obligations?

7) When Marmee is speaking of her husband’s enlisting in the army, she makes a very eloquent statement: “A sacrifice such as his is called noble by the world. But the world will not help me put back together what war has broken apart” (p. 210). Do her words have resonance in today’s world? How are the people who fight our wars today perceived? Do you think we pay enough attention to the families of those in the military? Have our opinions been influenced at all by the inclusion of women in the military?

8) The war raged on for several years after March’s return home. How do you imagine he spent those remaining years of the war? How do you think his relationship with Marmee changed? How might it have stayed the same?

In her memoir, Foreign Correspondence, we see how author Geraldine Brooks rebels against and then embraces her secure and rooted upbringing in suburban Sydney, Australia. Brooks becomes a foreign correspondent who travels from war zone to famine and finally arrives at a deeper understanding of the value of family, home, and stability in every person’s life. She tells that story in a way that carries her distinct stamp: she looks at the lives of others.

Throughout her childhood in the turbulent 1960s and 1970s (turbulent almost everywhere but Australia it seemed to a young Brooks) she corresponded with pen pals around the world. More than twenty years later, Brooks is surprised to find that her father has saved those letters. After reading them, she wonders what became of those childhood correspondents, and she decides to find out.

Traveling from Maplewood, New Jersey, to Nazareth, Israel, to St. Martin de la Brasque, France, to a New York City nightclub, Brooks tracks down her pen pals. While doing so she hears stories that cross latitudes and include tales of conscription, anorexia nervosa, peace, security, death, provincialism, and family. She also learns that she and her former correspondents, all grown up now, want many of the same things, and most have little to do with the excitement that she craved when she was a young girl.

As Brooks writes of her former pen pals, “[O]ne of them is dead, one is famous, one has survived wars, one overcome prejudice. And of all of them, it is Janine, living undramatically in the narrow circumference of her tiny village, whose life now seems to me most enviable.”

Geraldine Brooks can be contacted through:

You can contact Geraldine Brooks through Carolyn Coleburn at Penguin Random House by email:

ccoleburn@penguinrandomhouse.com

For speaking invitations, email Alysyn Reinhardt at Penguin Random House Speakers Bureau:

areinhardt@penguinrandomhouse.com

To see what Geraldine is thinking about today, go to her Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/GeraldineBrooksAuthor

Media Gallery

(Photographer’s credit must appear with Geraldine’s portraits wherever they are used)

“CALEB’S CROSSING” could not be more enlightening and involving. Beautifully written from beginning to end, it reconfirms Geraldine Brooks’s reputation as one of our most supple and involving novelists.” —JANE SMILEY, The New York Times Book Review

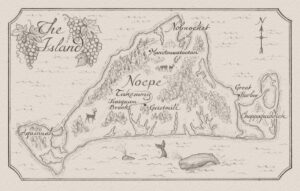

A richly imagined new novel from the author of the New York Times bestseller, People of the Book.Once again, Geraldine Brooks takes a remarkable shard of history and brings it to vivid life. In 1665, a young man from Martha’s Vineyard became the first Native American to graduate from Harvard College. Upon this slender factual scaffold, Brooks has created a luminous tale of love and faith, magic and adventure.

The narrator of Caleb’s Crossing is Bethia Mayfield, growing up in the tiny settlement of Great Harbor amid a small band of pioneers and Puritans. Restless and curious, she yearns after an education that is closed to her by her sex. As often as she can, she slips away to explore the island’s glistening beaches and observe its native Wampanoag inhabitants.

At twelve, she encounters Caleb, the young son of a chieftain, and the two forge a tentative secret friendship that draws each into the alien world of the other. Bethia’s minister father tries to convert the Wampanoag, awakening the wrath of the tribe’s shaman, against whose magic he must test his own beliefs. One of his projects becomes the education of Caleb, and a year later, Caleb is in Cambridge, studying Latin and Greek among the colonial elite. There, Bethia finds herself reluctantly indentured as a housekeeper and can closely observe Caleb’s crossing of cultures.

Like Brooks’s beloved narrator Anna in Year of Wonders, Bethia proves an emotionally irresistible guide to the wilds of Martha’s Vineyard and the intimate spaces of the human heart. Evocative and utterly absorbing, Caleb’s Crossingfurther establishes Brooks’s place as one of our most acclaimed novelists.

Reviews

“Brooks filters the early colonial era through the eyes of a minister’s daughter growing up on the island known today as Martha’s Vineyard…[Bethia’s] voice – rendered by Brooks with exacting attention to the language and rhythm of the seventeenth century – is captivatingly true to her time.” —The New Yorker

“A dazzling act of the imagination. . .Brooks takes the few known facts about the real Caleb, and builds them into a beautifully realized and thoroughly readable tale…this is intimate historical fiction, observing even the most acute sufferings and smallest heroic gestures in the context of major events.” —Matthew Gilbert,The Boston Globe

“In Bethia, Geraldine Brooks has created a multidimensional, inspiring yet unpredictable character…Bethia’s forbearance, her quiet insistence, the way she creates her life using the best of whatever is handed to her, puts the struggles of American women today in perspective.” —Susan Salter Reynolds, The Los Angeles Times

“Original and compelling. . .[Brooks’ characters] struggle every waking moment with spiritual questions that are as real and unending as the punishing New England winters.”—Paul Chaat Smith, The Washington Post