More Reading

Viking Books asks Geraldine Brooks some fascinating questions about her new novel, Horse.

HORSE is based on a real-life racehorse named Lexington, one of the most famous thoroughbreds in American history. How did you learn about him?

I had just published my novel, Caleb’s Crossing, which was partially researched at Plimoth Plantation, and the curators there had invited me to a lunch, at which they suggested I might want to write a novel based on a young woman from the early Plimoth settlement. It was clear to me that this would be too close to the character I’d already created in Caleb’s Crossing but from across the table I began to catch snatches of a different conversation. An executive from the Smithsonian was describing how he had just overseen delivery of Lexington’s skeleton from Washington DC to the International Museum of the Horse in Kentucky, where it would be the centerpiece on the history of thoroughbred racing in the US. As he related the horse’s extraordinary life story, I became fascinated, and by the time he got to the horse’s fate in the Civil War, I knew that my next book wouldn’t be about a settler in Plimoth, but about this horse.

Why the title?

When Lexington died, the horse was so beloved he was given a ceremonial burial, complete with a horse-sized coffin. Later, it was suggested that his skeleton be disinterred and gifted to the Smithsonian. It stood in pride of place there for many years. But as the horse’s fame waned and the museum’s emphasis switched from displaying curiosities to advancing scientific knowledge, Lexington’s individual story became less important, until the skeleton stood in the Hall of Osteology along with those of other species, simply an example of “equus caballus”, or “Horse.” Eventually it was relegated to the attic of the natural History Museum and all but forgotten.

It’s clear in the novel how central horseracing was in the 1850s, a passion as much in the North as the South, among Black Americans as White Americans. Why do you think it was so popular?

Before the Civil War and the Jim Crow era that followed Reconstruction, the racetrack was an integrated space, where all classes and colors mingled. Horseracing was the popular pastime of the 1800s, with crowds of twenty thousand or more packing racetracks to watch famous rivals such as Eclipse and Fashion, Grey Eagle and Wagner, and thousands of fans following the outcome in the lively turf press of the day. Of New York’s three main newspapers of the era, two were devoted entirely to horseracing. America was an agrarian culture; even most townsfolk were only a generation removed from the land. Races happened everywhere. Andrew Jackson raced his horse in the streets of Washington DC; many towns hosted quarter mile sprints on their Main Streets, and farmers of modest means dreamed of breeding the next champion. Meanwhile, the wealthy built racetracks on their plantations and saw in their thoroughbreds a reflection of their own prestige.

What is known about the enslaved people whose skills the racing business was built on? What sources did you have, and how much was left to the imagination?

Horseracing relied on the plundered labor of highly skilled Black trainers, jockeys and grooms. Their centrality is evident in the surviving correspondence of elite White horse breeders, who counted on the expertise of these men. These letters, as well as reporting in the turf press, reveal deference to the knowledge and skill of trainers such as Hark, Ansel Williamson and Charles Stewart and jockeys such as Abe Hawkins and Cato. These were great professionals who, within a brutal system, wrested a degree of personal agency not available to most enslaved people, including acquiring property and traveling widely throughout the country. Unfortunately, most of what we know of them is distorted through a White lens: Charles Stewart, for example, related his life story to a White woman and while the account is rich in detail, it is likely that he self-censored aspects that reflected badly on her forebears.

The central story involves Jarrett, an enslaved boy, and Lexington, the racehorse he raises and trains. What inspired his character and his story?

There are detailed accounts of a lost painting by the artist Thomas J. Scott (who is also an important character in the novel) depicting Lexington “being led by black Jarret, his groom” while the horse was at Woodburn Stud, which was perhaps the preeminent livestock breeding operation in America at the time. I was unable to find any biographical detail on Jarret, so I created his character based on records I could find about two highly accomplished Black horsemen who, though enslaved, were in charge of Woodburn’s thoroughbred operations: the trainer Ansel Williamson and the jockey and trainer Edward D. Brown.

The novel features a nearly contemporary storyline, set right before the pandemic, and an interracial relationship at the heart of it. As a historical novelist, why did you choose to write in the present day?

Just as my novel People of the Book has a contemporary thread in dialogue with its historical core, I wanted this novel to take us into the modern laboratories at the Smithsonian where bones are studied and artworks are evaluated. As I researched the historical spine of the novel it became clear to me that the story I’d thought would be about a racehorse was also a story about race, and as White supremacists rioted in Charlottesville and George Floyd died under the knee of a White police officer, I knew I could not deal with racism in the past and not address its loud and tragic echoes in the present.

You made another discovery related to the horse while you were researching at the Smithsonian, but this one was about art, not science.

Yes. One of the best surviving portraits of Lexington, painted by Thomas Scott, was given to the Smithsonian in a bequest from the pioneering gallerist, Martha Jackson. She was a friend of Pollock and DeKooning and a champion of avant garde art in 1950s New York City. It’s the only traditional, representational painting in her bequest–very different from the art she loved and collected. The mystery of why that painting might have mattered to Martha brings the novel into the turbulent, bohemian, post-war art world at the birth of abstract expressionism.

Who are the famous horses who descend from Lexington?

Ulysses S. Grant’s favorite horse, Cincinnati; the horse Preakness after whom the stakes race is named and two other Preakness winners; nine of the first fifteen Travers Stakes winners,; Asteroid, who was undefeated; Kentucky, who is in the US Racing Hall of Fame. Lexington sired 236 winners at a time when racing was disrupted by the Civil War and many thoroughbreds were requisitioned as warhorses. He appears in the bloodlines of many of the greatest racehorses even today.

You dedicate the novel to your late husband, the writer Tony Horwitz, and write in your Afterword that you traveled together to Kentucky, where your research often intersected in intriguing ways. Would you describe some of those intersections?

Tony was researching the travels of Frederick Law Olmsted just before the Civil War. Olmsted was interested in the views of the emancipationist Cassius Clay, who also happened to be the son-in-law of Lexington’s breeder, so we traveled together to Clay’s estate, White Hall. Tony also knew his way around the rich archival sources in Kentucky and was able to help me unearth a Civil War journal by the chaplain of Thomas Scott’s unit, which contained a detailed memoir of the two men’s relationship, forged in field hospitals caring for the wounded.

You ride horses and thank your horse Valentine and her companion who “were daily inspirations.” When did you begin riding?

Late! I was in my 50s when I took my first riding lesson, a time when knitting lessons might perhaps have been a more prudent choice. I’m still not a very good rider, but there’s so much more to horses. They’re exquisitely sensitive animals who can teach us a lot about ourselves, about group dynamics, and about leadership. Valentine and I have volunteered in a therapeutic riding program for children with autism and sometimes the relationship between child and horse verges on the miraculous. That’s why it’s tragic that so many racehorses are used up and destroyed before they’re five. My horse is twenty-six and she still has so much to give.

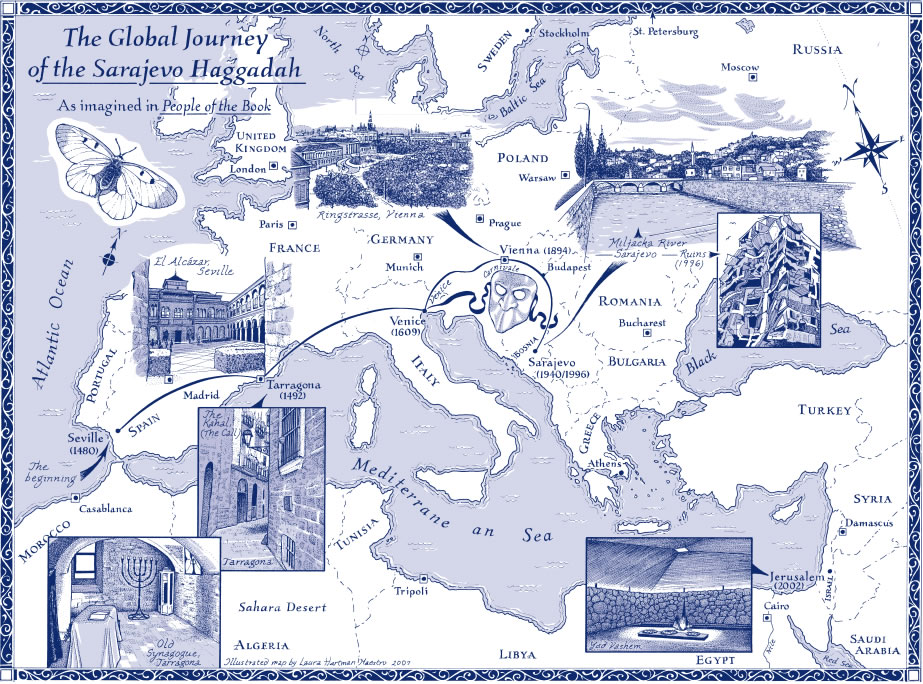

This map is from the inside cover of People of the Book. It was designed by Laura Hartman Maestro. This is for personal use only and may not be reproduced or distributed without written permission. If you would like to use this for your reading group please contact us first.

With her critically acclaimed and bestselling novel Year of Wonders, Geraldine Brooks was praised for her passionate rendering and careful research in vividly imagining the effects of the bubonic plague on a small English village in the seventeenth century. Now, Brooks turns her talents to exploring the devastation and moral complexities of the Civil War through her brilliantly imagined tale of Mr. March, the absent father from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. In Mr. March, Brooks has created a conflicted and deeply sensitive man, a father who is struggling to reconcile duty to his fellow man with duty to his family against the backdrop of one of the most grim periods in American history.

With her critically acclaimed and bestselling novel Year of Wonders, Geraldine Brooks was praised for her passionate rendering and careful research in vividly imagining the effects of the bubonic plague on a small English village in the seventeenth century. Now, Brooks turns her talents to exploring the devastation and moral complexities of the Civil War through her brilliantly imagined tale of Mr. March, the absent father from Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. In Mr. March, Brooks has created a conflicted and deeply sensitive man, a father who is struggling to reconcile duty to his fellow man with duty to his family against the backdrop of one of the most grim periods in American history.

October 21, 1861. March, an army chaplain, has just survived a brush with death as his unit crossed the Potomac and experienced the small but terrible battle of Ball’s Bluff. But when he sits down to write his daily missive to his beloved wife, Marmee, he does not talk of the death and destruction around him, but of clouds “emboss[ing] the sky,” his longing for home, and how he misses his four beautiful daughters. “I never promised I would write the truth,” he admits, if only to himself.

When he first enlisted, March was an idealistic man. He knew, above all else, that fighting this war for the Union cause was right and just. But he had not expected he would begin a journey through hell on earth, where the lines between right and wrong, good and evil, were too often blurred.

For now, however, he has no choice but to press on. He is directed to a makeshift hospital, an old estate he finds strangely familiar. It was here, more than twenty years earlier, that he first met Grace, a beautiful, literate slave. She was the woman who provided his first kiss and who changed the course of his life.

Now, he finds himself back at the Clement estate, and what was once the most beautiful place he had ever seen has been transformed by the ugliness of war. However, March’s sojourn there is brief and he finds himself reassigned to set up a school on one of the liberated plantations, Oak Landing—a disastrous posting that leaves him all but dead.

Though rescued and delivered to a Washington hospital where his physical health improves, March is a broken man, haunted by all he has witnessed and “a conscience ablaze with guilt” over the many people he feels he has failed. And when it is time for him to leave he finds he does not want to return home. He turns to Grace, whom he has encountered once again, for guidance. “None of us is without sin,” she tells him. “Go home, Mr. March.” So, March returns to his wife and daughters, and though he is tormented by the past and worried for his country’s future, the present, at least, is certain: he is home, he is a father again, and for now, that will be enough.

Questions for Discussion

1) Throughout the novel, March and Marmee, although devoted to one another, seem to misunderstand each other quite a bit and often do not tell each other the complete truth. Discuss examples of where this happens and how things may have turned out differently, for better or worse, had they been completely honest. Are there times when it is best not to tell our loved ones the truth?

2) The causes of the American Civil War were multiple and overlapping. What was your opinion of the war when you first came to the novel, and has it changed at all since reading March?

3) March’s relationships with both Marmee and Grace are pivotal in his life. Discuss the differences between these two relationships and how they help to shape March, his worldview, and his future. What other people and events were pivotal in shaping March’s beliefs?

4) Do you think it was the right decision for March to have supported, financially or morally, the northern abolitionist John Brown? Brown’s tactics were controversial, but did the ends justify the means?

5) “If war can ever be said to be just, then this war is so; it is action for a moral cause, with the most rigorous of intellectual underpinnings. And yet everywhere I turn, I see injustice done in the waging of it,” says March (p. 65). Do you think that March still believes the war is just by the end of the novel? Why or why not?

6) What is your opinion of March’s enlisting? Should he have stayed home with his family? How do we decide when to put our principles ahead of our personal obligations?

7) When Marmee is speaking of her husband’s enlisting in the army, she makes a very eloquent statement: “A sacrifice such as his is called noble by the world. But the world will not help me put back together what war has broken apart” (p. 210). Do her words have resonance in today’s world? How are the people who fight our wars today perceived? Do you think we pay enough attention to the families of those in the military? Have our opinions been influenced at all by the inclusion of women in the military?

8) The war raged on for several years after March’s return home. How do you imagine he spent those remaining years of the war? How do you think his relationship with Marmee changed? How might it have stayed the same?

In your afterword, you make an amusing apology to your husband, a well-known writer and Civil War afficionado, for your previous lack of appreciation for his passion. Although you say you’re not sure “when or where” it happened, would you talk a bit about your change of heart and what led to your new and profound interest in the American Civil War and eventually to the writing of March?

In the early 1990s we came to live in a small Virginia village where Civil War history is all around us. There are bullet scars on the bricks of the Baptist church where a skirmish took place; we have a Union soldier’s belt buckle that was unearthed near the old well in our courtyard. The village was Quaker, and abolitionist, but in the midst of the Confederacy. The war brought huge issues of conscience for the townsfolk, a few of whom sacrificed their nonviolent principles to raise a regiment to fight on the Union side. It was thinking about the people who once lived in our house, and the moral challenges the war presented for them, that kindled my interest in imagining an idealist adrift in that war. I am gripped by the stories of individuals from the generation Oliver Wendell Holmes so eloquently described when he said: “In our youth our hearts were touched with fire.” I’m still not all that interested in the order of battles, I still drive Tony crazy by failing to keep the chronology straight, and offered the choice between a trip to the dentist and another midsummer reenactment, it’d be a hard call. But sometimes, alone on a battlefield as the mists rise over the grass, I feel like a time traveler, born back by the ghosts of all those vivid, missing boys.

Grace Clement is such an extraordinary character and is pivotal in shaping March’s life. You tell us that her voice was inspired by an 1861 autobiography, but what inspired you to create a romantic relationship between Grace and March? Were there any historical hints that Alcott had had such a relationship?

The idea of an attraction between March and Grace is entirely imagined and not at all suggested by Bronson Alcott’s biography. It grew naturally out of the narrative: they are young and attractive when they first meet, he is an idealist, she is a compelling person in a dramatic and moving situation. It seemed inevitable to me.

A year after March enlists he says, “One day I hope to go back. To my wife, to my girls, but also to the man of moral certainty that I was . . . that innocent man, who knew with such clear confidence exactly what it was that he was meant to do.” Do you think he can go back? Is it even possible? Would you discuss how you think March changes by the end of the novel and what parts of him remain intact?

I don’t think he can go back. Nor do I think it is necessarily desirable. Moral certainty can deafen people to any truth other than their own. By the end of the book, March is damaged, but he is still an idealist; it’s just that he sees more clearly the cost of his ideals, and understands that he is not the only one who must pay for them.

Your book Nine Parts of Desire deals with the issues of Muslim women. Year of Wonders had a female heroine, Anna Frith. How was it different writing principally from a man’s point of view this time?

I have always believed that the human heart is the human heart, no matter what century we live in, what country we inhabit, or what gender we happen to be. This is a book about strong feelings: love and fear. I can’t believe there’s much difference in how a man or a woman experiences them. And then, I had the journals and letters of Bronson Alcott, which are perhaps as complete a record of a Victorian man’s interior life as any you could find.

It is quite a surprise to suddenly hear Marmee’s voice in Part Two. Can you talk about how and why you decided to change the point of view here?

The structure of March was laid down for me before the first line was written, because my character has to exist within Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women plotline. That meant March has to go to the hospital gravely ill and Marmee has to arrive to tend him. The alternative to switching voices would have been to continue the narrative in March’s voice, disoriented by his delirium. But giving Marmee a voice seemed like an opportunity to me to better explore some of the themes of communication, and miscommunication, in a marriage. Also, the book was written against the tumult of my own feelings about the war with Iraq, and as I started to write in Marmee’s voice I found that she could naturally articulate a frustration, grief, and confusion that seemed in common between us.

The American Civil War was enormously complex with different political, social, economic, and psychological factors all playing a role. What did you learn from your research that may have surprised you and, other than your obvious newfound interest, is your opinion of the war any different now than when you started?

Nations inevitably fall into the trap of romanticizing their militaries and are always astonished when the truth of awful atrocities is revealed, as it inevitably is in almost every war. There were plenty of hate-filled racists in Lincoln’s army, fighting side by side with the celebrated idealists. March’s growing dismay as he learns this in a way reflects my own journey to a more complete understanding.

Would you talk a bit about how your past work as a foreign correspondent informs your current writing? What do you think historical fiction can achieve that nonfiction cannot? Would you ever entertain the idea of writing a novel about current events?

Write what you know. It’s the first advice given to writers. I did draw on some experiences of war from my correspondent years. You see things during war, and you can never unsee them. The thing that most attracts me to historical fiction is taking the factual record as far as it is known, using that as scaffolding, and then letting imagination build the structure that fills in those things we can never find out for sure. And to do that you use all the experiences you can. While I love to read contemporary fiction, I’m not drawn to writing it. Perhaps it’s because the former journalist in me is too inhibited by the press of reality; when I think about writing of my own time I always think about nonfiction narratives. Or perhaps it’s just that I find the present too confounding.

What are you working on now?

Another historical novel based on a true story, but one where the truth is not completely known, and so there are intriguing voids for the imagination to fill. Like March andYear of Wonders it has a lot to do with faith and catastrophe.

In her memoir, Foreign Correspondence, we see how author Geraldine Brooks rebels against and then embraces her secure and rooted upbringing in suburban Sydney, Australia. Brooks becomes a foreign correspondent who travels from war zone to famine and finally arrives at a deeper understanding of the value of family, home, and stability in every person’s life. She tells that story in a way that carries her distinct stamp: she looks at the lives of others.

Throughout her childhood in the turbulent 1960s and 1970s (turbulent almost everywhere but Australia it seemed to a young Brooks) she corresponded with pen pals around the world. More than twenty years later, Brooks is surprised to find that her father has saved those letters. After reading them, she wonders what became of those childhood correspondents, and she decides to find out.

Traveling from Maplewood, New Jersey, to Nazareth, Israel, to St. Martin de la Brasque, France, to a New York City nightclub, Brooks tracks down her pen pals. While doing so she hears stories that cross latitudes and include tales of conscription, anorexia nervosa, peace, security, death, provincialism, and family. She also learns that she and her former correspondents, all grown up now, want many of the same things, and most have little to do with the excitement that she craved when she was a young girl.

As Brooks writes of her former pen pals, “[O]ne of them is dead, one is famous, one has survived wars, one overcome prejudice. And of all of them, it is Janine, living undramatically in the narrow circumference of her tiny village, whose life now seems to me most enviable.”